Apocalypse Now Redux

Keyboard Magazine interview with Ed Goldfarb, 2001 by Ken Hughes

Released in 1979, Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now was one of the first major films to use synthesizers as a central element of the score. Twenty years later, when Coppola began working on an extensively revised and expanded “directors cut,” since released to theatres as Apocalypse Now Redux, some unique problems cropped up. The music Coppola’s dad Carmine had composed for some deleted (now re-inserted) scenes was never finished.

Carmine’s orchestral score was realized on synthesizers in the late ’70s, and the new cues had to sonically match the existing cues, but information on which synths were used for which signature sounds was sketchy or nonexistent. To make matters worse, Carmine Coppola is no longer living, so he couldn’t be consulted.

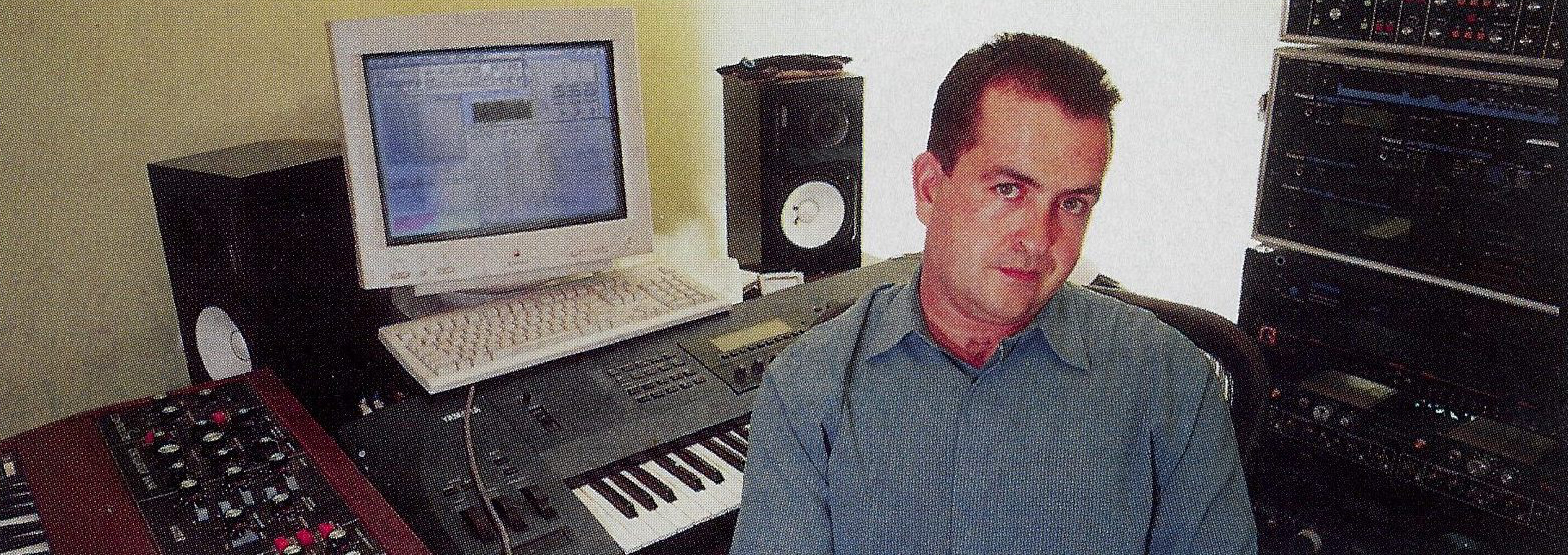

Francis Ford Coppola turned to his longtime associate, Bay Area composer/producer Ed Goldfarb, to pull it all together. Keyboard caught up with Goldfarb at his deceptively lean Marin County studio.

Keyboard: I notice there’s no video deck or SMPTE equipment here. How did you score the new scenes?

Ed Goldfarb: Zoetrope [Coppola’s film company, American Zoetrope] sent me a videotape of rough dubs. I had an Aurora Fuse video capture card, which didn’t even have audio. I threw the video in there, ran the audio into Digital Performer, lined ’em up just by watching Martin Sheen talk or whatever, checked the clip at both ends to make sure there was no drift, set DP’s start time from the window dub [a window of timecode readout superimposed on the video footage], and away I went. I created my own two-pop [a short sound burst which occurs exactly two seconds prior to the start of the music cue — used to help line up cues during sound editing]. No one has ever asked me for anything different or had any problems with this.

When the project moved from my studio to the Zoetrope studio for the mix, I burned CDs of audio tracks starting with the two-pop, and the engineer just lined ’em up. It took seconds in Pro Tools. There’s a theme that will emerge, and that theme is low-tech. A lot of people think, “If I’m gonna do video or film scoring I need to go out and buy a 3/4″ U-Matic video deck, have three-way lockup, and get a blackburst generator.” Well, you don’t need all that.

I’ve created stuff for Roman Coppola that was all done “virtually.” They emailed a QuickTime movie of the visuals to me and I created the score based on that. I conducted the musicians while watching the QuickTime window in Digital Performer, recording them to disk. When I was finished, I mixed it right there on the computer and FTP’ed it to Australia. It was shown to the client, an Australian ISP, immediately. Everything synced up perfectly. We don’t need SMPTE anymore. I never had the video in my hand. I’ve been doing things this way for ten years and have never had a sync problem.

You did all your score work in a QuickTime window on that tiny little monitor there?

That’s right. There’s a little bit of a challenge in imagining the scope of something like Apocalypse Now when you’re looking at this ridiculous little window, but it gets the job done. If… no, when I score a whole feature myself, I’ll probably set up a second monitor just for the picture.

How much information did you have about how the original score was done? Was it difficult to make your new realizations blend in seamlessly?

Since the cues existed by themselves — there were no tight segues to other cues, only crossfades and whatever — it was a lot easier. They hooked me up with a DVD of the film. I was familiar with the movie anyway; I’ve always been a film buff. I always thought of the Rhythm Devils, Mickey Hart’s drum group, and of course “Ride of the Valkyries,” when I thought about the music in this film. When I went back and studied it in preparation for the re-release, the synth music sounded a lot like [Japanese synthesist Isao] Tomita to me.

As it turns out, Francis’s original concept for the score, which is brilliant, was to have Carmine compose the score for orchestra, and then have Tomita realize it for synthesizers. There’s a cue about two-thirds of the way into the movie where it’s obvious that the temp music [music used as a placeholder, usually strongly having the vibe the director wants to hear in the final score] was Tomita’s version of the first movement of Holst’s The Planets—”Mars, The Bringer of War.” What Carmine did was to sort of cop that feel, in the time-honored Hollywood tradition [laughs].

Francis did meet with Tomita to discuss the project, but Tomita was famous at the time for taking an extraordinary amount of time to complete new works; when you’re doing string sections by overdubbing monophonic violin lines, it just takes time, you know? When it became clear that that idea was not going to work [the production of Apocalypse Now was infamously, hopelessly behind schedule already], Francis handed it off to a bunch of synthesists in the Bay Area, and had David Rubinson, who ran the Automatt studio in San Francisco, produce the score. Nyle Steiner came in with his experimental EVI [Electronic Valve Instrument] late in the game and played the main three-note motif that’s used throughout the film. Francis co-wrote the music by singing ideas to his dad the same way he did with me many years later. He actually has an amazing musical mind. Recently, in the midst of all the other hundred and one things he’s got going on, he learned how to write melodies on manuscript paper. He’s quite the Renaissance man.

Redux is the cut that Francis always wanted to release. Now that the film is part of cultural lore, he wanted to go back and make the version that he always wanted. Carmine had orchestrated part of the score for the French plantation sequence, which is the single biggest chunk of deleted work recut into the film, but it was never recorded. For the rest of the sequence, there were only piano sketches.

When I got the gig, I made a trek up to the Coppola archives in Napa, and brought back two big boxes full of Apocalypse manuscripts and synthesis notes and track sheets and what-have-you. But there weren’t any indications of what synths were used. From listening to cues on the DVD, and from doing record production and geeking out on equipment, I now have a pretty good ear for what did what. I could kinda tell, okay, that’s a Minimoog, that’s a double-tracked ARP String Ensemble, that’s four Minimoogs, here they’re abusing a Urei 1176, and so on.

We ended up extending the rules a little bit to include not only gear that was used in the original score, but also gear that could have been used in 1979. Francis is surprisingly mellow about this whole process. There wasn’t a directive that I had to be faithful to period gear and techniques. He just said, “Make sure it sounds like Apocalypse.” My interpretation of that was, “Well, let’s figure out how they did it then and do that now.” I used a celeste in one of the cues; it doesn’t appear anywhere else in the score, but it was available in 1979, so it was fair game.

I have an Oberheim Xpander, and a Minimoog, and a [Studio Electronics] SE-1, and a Mellotron, so I was able to do a bunch of things right. I borrowed an ARP String Ensemble. I also went to the old multitracks, but they were noisy because they were done with Dbx and I didn’t have a Dbx deck. The track sheets were a big help, though. I could see what was double-tracked and whatever.

The biggest help was listening to Tomita records, since it was his style that the 1979 synthesists were copping.

One of Francis’s ideas back in the day was to use the sound of cicadas for strings, and mortar shells for timpani. Sounds that were part of the environment in Vietnam. You could do it now, but there wasn’t enough time and it wouldn’t have blended with the existing score. We’d have had to redo the whole score. I made a couple of little sketches of that kind of thing, and we agreed that it was exciting, and that there was no way to integrate it and have it work. It’s interesting that he thought of that back then.

How did you get this gig?

I’ve been Francis’s go-to guy for certain things for several years. I started working with him in 1995. That came about when I was music director at Beach Blanket Babylon, and Francis was friendly with the late Steve Silver, who created Beach Blanket. They were both part of the San Francisco arts community. Francis mentioned to Steve that he needed a couple of pianists for a project on which he was thinking about using some of his father’s compositions.

Francis needed people to sight-read and play through these reams of music. I showed up very nervous, more well-dressed than I usually am, and with my Dictaphone. I played through some of the music … sight-reading is kinda what I do. I never spent much time playing baseball as a kid. Francis and I hit it off. He has a son my age, I have a dad his age, Italians, Jews, you know… They’ve got better food, but we agree on most things.

He mentioned that he had been thinking about some tunes of his own. I didn’t know he composed. He ended up singing a couple of tunes he’d been playing with for this project into my Dictaphone and I thought, hey, this is my moment. I went home and worked through the night doing a MIDI orchestration of the tunes he’d hummed into the Dictaphone. Francis wasn’t even really aware you could do that, so it was very exciting for him to hear.

Overnight, you brought him what he heard as a full orchestral arrangement of this music he had sung to you.

Yeah. To make a long story short, I ended up getting put on the Zoetrope payroll to work with him as a musical interpreter on what turned out to be Pinocchio, about which there was a lot of buzz at the time, a lot of money was spent, there was a lawsuit at one point… I orchestrated a whole show’s worth of music and then some, all Coppola compositions.

You bring in this orchestration, and what? His jaw drops?

Well, when Francis is excited about something, he’ll say [imitates Brando as the Godfather], “That’s very impressive.” He’s seen it all. But he was very impressed by the technology that allowed me to do it. He’s really tech-savvy in some areas and maybe less so in others. For instance, he was the first guy after George Lucas to start using the EditDroid [digital film editing system, now known as Avid], but he wasn’t necessarily up on all the MIDI stuff.

Over a period of about three years, we worked on Pinocchio. I brought in singers, and I was able to do a bunch of really cool MIDI orchestration things. All of it was for naught. The film was never made. It was a shame, because it was shaping up to be really great. It was extraordinary to see how much preproduction actually went on before the plug got pulled. I remember meeting the team of animators, being in on character meetings. We assembled a full storyboard with a soundtrack. All the dialog was recorded. The Columbia people came up; we were all very excited. We even distributed a big booklet of the sheet music itself, which Francis was very proud of, but it was not to be.

I did a few things for his summer theatre workshop in Napa, and a bunch of other projects. I worked on the set of the movie Jack with Robin Williams. Anytime anyone sang onscreen, I was their coach. That was interesting. Then one day I just got the call for Apocalypse Now Redux.

Tell us a little more about the cues you realized for Apocalypse Now Redux.

There’s a funeral and a love scene that take place within this French plantation sequence. Carmine had sketched the funeral, and where the score said flutes, or strings, I would just try to do what Tomita might have done. Also, there’s a cornet playing taps. I wanted to incorporate the onscreen sound into the score. Well, the horn was flat. We put it into ProTools and pitch-shifted it. Actually, we had to edit the performance too, because not only was the horn flat, but the intonation was off. It was kind of nice to be able to do that.

I sequenced everything in DP. Then I delivered stems [submixes]; stereo strings, flutes with the echo, and all that. For the second cue, there was only a piano sketch — a melody and some chord shapes. Francis and I worked together on the orchestration. He might suggest that the flute be doubled by the strings, that kind of thing.

Was there any specific sound from the lexicon of sounds used in the film that was particularly difficult to recreate?

Timpani were kind of difficult. I dissected some timpani sounds in my Roland MKS-50 to see how they did it, and it was sort of a ring modulator type of thing. I ended up using my SE-1 in two passes for timpani parts. First I synthesized the attack component, and then the tone, and I just ran the same sequence twice to get them together. I’d love to know more about the people who did the original work, because it was really good. They did a decent-sounding Tomita imitation on what I imagine was a fairly restrictive budget, and they turned it around pretty quickly.

It helps that the score is kind of all over the map anyway — you’ve got this synthesized orchestra done by a bunch of individuals who collaborated but didn’t really work together, you’ve got Mickey Hart’s improvisational percussion stuff, you’ve got Randy Hansen doing the Hendrix guitar thing, you’ve got Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” there’s all kinds of stuff in there.

Was there ever a moment where you were really put to the test?

I actually ended up having to do a bunch of overdubs at the mixing stage at the last minute. We were listening to the second cue, and Francis said, “We need more. There’s not enough stuff going on. I hear flutes, and harps…”

I had brought a three-octave mini-keyboard and a [Roland] ]V—1080, thinking that we might need to do a little something. Well, that cue is rubato, there was no click, so I’m sitting there with this stupid little keyboard while [film editor/sound designer] Walter Murch, the tech VP at Zoetrope, Kim Aubry, Francis, and, like, eight other heavies are there. God only knows what this is costing hourly. All your life has been leading to this [laughs]. Francis wanted a harp, but I couldn’t just dial up a harp sample. I had to program up an analog harp so it would blend in. That was fun.